![The Institute for the Less Good Idea]()

Visiting William Kentridge at his Johannesburg studio.

Financial Times magazine, 2 September 2016. PDF.

My (longer) edit, with The Nose reinstated:

I knew I was at the right place because of the cats. Two sculpted, spiky creatures faced each other atop the gates in Houghton, one of Johannesburg’s wealthy, jacaranda-shrouded suburbs. I recognized them from drawings, etchings and films – in which cats emerge from radios (Ubu Tells the Truth), curl into bombs (Stereoscope), turn into espresso pots (Lexicon). Now they had become metal, swinging open to reveal a steep driveway and above it a brick and glass building perched on stilts amid foliage: the studio. A gardener directed me past some cycads to the right entrance and there an assistant ushered me in to meet William Kentridge. He was wearing a blue rather than a white collared shirt, but in all other aspects conformed to his self-appointed uniform: black trousers, black shoes, the string of a pince-nez knotted through a button hole, the lenses stowed in a breast pocket when they were not on his nose.

Read More

![Prince Pro]()

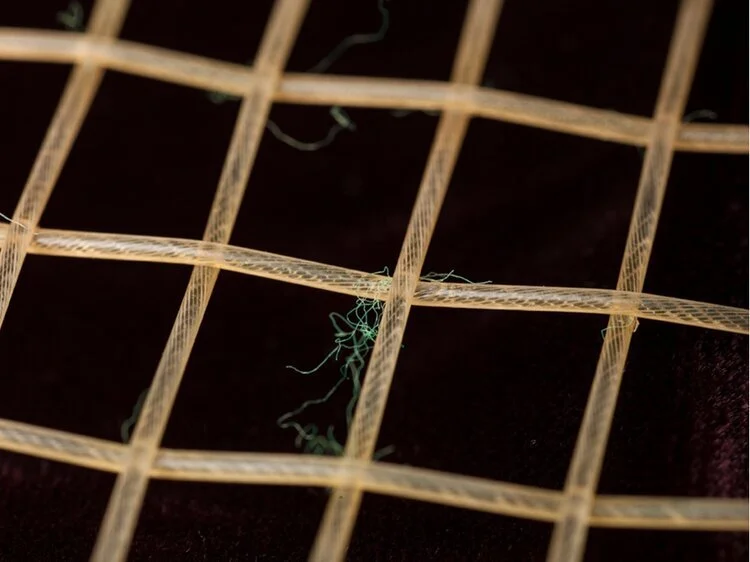

About my father's record collection and my mother's tennis racket.

In Object Relations: Essays and Images. Edited and photographed by Stephen Inggs. Michaelis School of Fine Art, 2014.

When I was 18 and finishing school abroad, my father went (I think) a little crazy. He began giving away all our things. This is, perhaps, understandable behaviour when you are retrenched from a company you never liked anyway, and then move to the opposite side of the country. But still, the scale of the purge stunned me.

First, the record collection. My father was at Leeds University during the 1960s, and often let it slip that Clapton, Hendrix and The Who had played in the student union, that it was no big thing back then. He had all their albums, with that luxuriant amount of space the LP format affords for artwork. Roger Daltrey in a tub full of Heinz baked beans (The Who Sell Out) and Carole King just kicking back at home with her cat (Tapestry). The original of Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band itself, complete with cardboard insert epaulettes and moustaches that you could anchor in your nose via little tags. The naked, languorous women spread over the gatefold cover of Electric Ladyland – for a small boy on a mining town on the far West Rand in the dying days of apartheid, this was a formative document.

And when the needle came down, the low-end kick of these records on an analogue stereo: Eddie Cochran's Summertime Blues, Simon and Garfunkel's Cecilia. It sent me into paroxysms of excitement.

Read More